I was always curious about bonsai pots the Japanese call Nanban. My recent residency at Fujikawa Kouka-en in Osaka fuelled my curiosity about them even further. After my return to Sydney, I wanted all the Nanban information I could get. My first impulse was to search the Net, which brought only disappointment. Then I remembered that John Naka had something about it in his “Bonsai Techniques II”. Sure enough the book has a couple of short paragraphs about Nanban containers, but it wasn't enough to quench my thirst for knowledge.

Usually my access to Japanese sources is non-existent, but this time I was lucky to find one. At Kouka-en nursery, I came across of the following book: Nippon Bonsai Association (1990) Masterpieces of bonsai pot art - Grand edition, Volumes I & II, Nippon Bonsai Association publication, Japan (美術盆器名品大成 , 日本盆栽協同組合編). These are two absolutely magnificent volumes. Unfortunately, the book is out of print, prohibitively expensive and in Japanese, which makes it somewhat inaccessible to the bonsai community outside Japan. Volume II has a section titled “Nanban”. Below is my interpretative translation of this section to English.

“The term Nanban referring to a particular kind of imported pottery is vague and difficult to classify. Due to Japan’s national isolation during the Tokugawa era, the precise meaning of the word Nanban, implying a foreign country in the South, is obscure. Some believe that it is a name for Taiwan, others think that it is a name of some other place in South-East Asia. In short, the majority considers China, Korea, India and surrounds to be the most likely places of Nanban’s origin.” This is a passage from an article by Zesora Kobayashi published in 1935 September issue of “Bonsai” magazine. The author was an eminent figure in the bonsai community, who brought Nanban pots into focus in this excellent article, which later became a great point of reference.

Nanban doesn’t refer to a particular country or production area. It was a collective term for certain artefacts used by tea masters in the world of art and antiques. Before the Meiji era, miscellaneous utensils of daily use have been brought over from the Southern seas for the tea masters of olden days. At first, these containers have been used as vessels for flower arrangement. Being highly prized, there was no way to satisfy the demand for them. Therefore at the request of tea masters, potters such as Ninami Dohachi, Hozen Eiraku, Mokubei Aoki and Miura Chikusen began making Nanban imitations. A wide range of Japanese-made Nanban imitations included pottery from Bizen and Ryukyuan Islands as well as Naeshirogawa ware of Satsuma and Shyodaiyaki ware of Higo. All of them are collectively referred to as Nanban.

The earliest Nanban containers entered bonsai scene before the Meiji period and were typically small round trough-shaped pots, dishes and jar lids, which were modified into a bonsai pot by drilling holes in their bottom. These were produced in Taiwan, Ryukyuan Islands, Luzon and according to Zesora Kobayashi in Southern China.

There are only few tribes among Taiwan aboriginals which knew pottery. One of them is the Yami tribe of the Orchid Island situated several dozen nautical miles off the southern coast of Taiwan. It is also said that the Ami tribe from the east coast plains of Taiwan, made yellowish colour ware referred to as "hannera". Very primitive brown Nanban pots are assumed to be from there. Apart from those, there were also seed storage jars brought from Taiwan. It is believed that they have been made in Xiamen, China and then brought to Japan via Taiwan.

During the thirty odd years between the 9th year of Keichō era (1613) and the 12th year of Kan'ei era (1636), Tokugawa Ieyasu issued official permits, allowing merchants to trade with Korea, Ming Empire, Luzon, Annam, Cambodia and other places. Sea voyages exploring coastal areas extended from Taiwan to Macau, Sumatra and Thailand. Some of the Nanban containers were brought to Japan during this period.

The age of Nanban pots is generally not essential. They are primarily admired and valued for their rustic grace and charm. At some point in the past, a bonsai aesthete realised that these qualities would complement bonsai. Unfortunately, the name of the person who introduced Nanban containers to bonsai is unknown. Soon after that however, Nanban containers became quite popular, while they were rather rare. Yonekichi Kibe of former Taikō-en bonsai nursery has been the lead driver of the Nanban popularity till the late Meiji period. In response to this popularity, Chinese merchants set up a production of containers imitating Nanban shape and appearance. They were mostly produced in Xiamen, Fujian from where they were shipped to Japan via Shanghai. This supply of Nanban containers to Japan continued throughout the pre-war period until 1941.

As explained above, it is not possible to ascertain the precise place of origin of Nanban ware due to their wide geographic spread. The only exception from Nanban category is the Yixing ware, despite of the fact that concave lids for large storage jars were produced there. They are excluded from the Nanban class because of the differences in texture and colour of the clay.

Nanban containers look primitive and amateurish, however making them requires sound craftsmanship. Its simplicity and spontaneity makes them a particularly natural choice for some bonsai, however one needs to overcome certain mental resistance to fully embrace Nanban as such a choice.

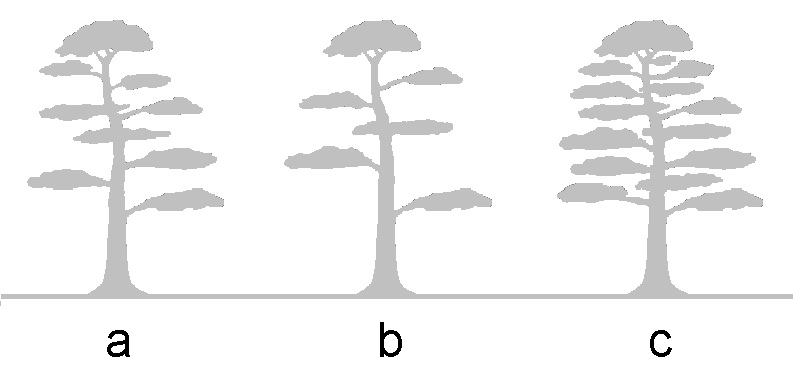

This passage is all I know about Nanban pots so far. Below are the illustrations which accompany the passage in the book. They should help you with a mental picture of Nanban containers.